I will credit Ms. Andrea Swartz as the studio professor whose approach has influenced me in regard to a rational approach to design. Her assignments pushed us to consider program, structure, materiality, and environmental factors in an iterative fashion, all the while exploring the conceptual basis for our decisions in each iteration. She called us out when we made arbitrary decisions, always pushing us to take our ideas beyond the surface level. I now find myself experiencing a certain level anxiety when I realize I've made a decision that I cannot defend conceptually.

Andrea also imparted a value for materiality that I want to continue to explore. She had us doing experiments with various materials from the start. As a result I found myself playing with a welder and constructing formwork for small designs in steel and concrete. The experience made me want to spend more time in the shop working with my hands, and it brought home the physicality and spatial presence that architecture realizes. I loved it. Coming from the computing field where everything is virtual, this was a breath of fresh air affirming my decision to make a career change.

In my process in studio I am seeing the value of analog methods beyond material explorations as well. Study models are great, taking me back to my Lego-building days where I can design as I build, try things out, take them apart and start over with minimal expense. I build using scraps as a way to short-circuit my perfectionist tendencies. Sketching is also essential, I find, for some of the same reasons. With a pen and trace paper I can iterate through ideas more quickly than any experiment on the computer.

This move to analog (i.e. non-digital) design makes me nervous since it's new territory; I'm so used to working on the computer. I see the problems with designing digitally, however. At this point the tools are too restrictive. Most modeling programs favor a certain type of geometry; some force early definition of details that are better left out at the beginning. They all easily consume a lot of time and changes to a design are typically painful, discouraging bolder exploration of ideas. At some point digital tools are indispensable of course. Parametric design can sometimes speed up design iterations and generate new ideas that would never come about through sketching.

I really value input from others in the design process--I know I need feedback from peers and mentors to hone my design and my process. I especially love the experience of collaborating with another designer who operates on the same wavelength. The synergy that develops in that kind of environment allows for greater leaps, fresh ideas and sped up design iterations in way that is quite exhilarating. I speak from my experiences with this kind of synergy in my former career and I have tasted it in discussions with others in the grad program with whom I share common interests. I hope to find this kind of energy in my career in architecture.

When it comes to my personal values in relation to architecture, I believe concepts of community will be central. My own experience with community has been that is an unparalleled source of love and healing. This a spiritual reality, one that I do not believe is truly possible apart from faith in God who provides the ability to love and accept one another in spite of faults and differences. I believe this kind of community can exist in any built environment--it is perhaps its most vibrant when forced to exist in inhospitable conditions, which require individuals to depend on each other to a greater degree.

The built environment may, however, be more or less conducive to the formation of community. Community may be able to thrive in any environment, but that does not mean it is unaffected by it. There is also a physical, day-to-day aspect of community that expresses a different kind of spirituality, that of presence. Our presence with one another day-in, day-out plays, I believe, an important role in individual spiritual and emotional healing, and this happens in physical space and time. Since the built environment is a significant part of our physical existence in time and space, it will be interesting to explore what role it plays in facilitating and encouraging (or discouraging) the formation of community. What creates a place of safety? What makes a space desirable for gathering? for intimacy? What are the social justice aspects? How does this manifest itself at the neighborhood level? Hmm, this sounds like the makings of a thesis...

Regardless of the project I believe there will opportunities for leadership, and I see myself stepping up to those opportunities and promoting the values that characterize my approach. Each project is a chance to set higher standards, to influence the industry, to improve a community, to respect the environment, to respond in a fashion sensitive to client, site, physical context, program, and social / cultural context. Given my desire to participate in community to this degree, I hope to one day form my own practice and be able to lead at that level as well.

Beyond the above values, there are a number of concepts and areas of interest that stimulate my thinking and excite me as avenues for future exploration. I like the idea of

- a work of architecture being a critique of something else - be it a social construct, a movement within the arts, a political movement, an architectural style or trend, etc.

- architecture as experience (phenomenology?), as prompting something spiritual, esp. as generated by the sensitive use of materials, by the formation of space, by directing and framing views, etc.

- permanence vs. impermanence--architecture creating continuity in a community by nature of its durability and material presence while acknowledging that everything decays

- adaptability through architecture that can be repurposed (or even recycled) with a minimum of waste; related to adaptive reuse - making use of existing building stock, repurposing existing structures in innovative ways

- simplicity in design, the result of numerous iterations toward finding the most elegant and efficient solution to a design problem; related, perhaps, to minimalism

- interactivity, often related to materiality, but also as realized by technology, esp. the field of human-computer interaction in the context of architecture

I have really enjoyed the readings on theory over the course of the semester, and so many of my interests are rich theoretically landscapes. The readings I've referenced in previous posts to this blog have been very gratifying, especially the readings on Mies and on Kahn, those on the Amsterdam School and De Stijl, and the one on Semper. My research on Hassan Fathy and Charles Correa broadened my knowledge and gave me valuable experience as I sought out sources to inform my analysis. All of these readings have influenced my thinking regarding a conceptual basis for architecture... I'm sure there will be more to come.

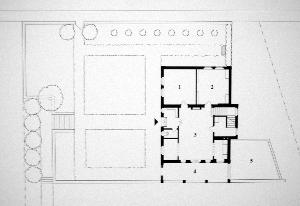

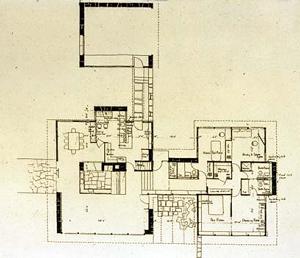

In terms of aesthetics, I'm not sure exactly where my affinities lie. They are diverse. I like a lot of the work of firms like Morphosis, SHoP Architects and Kieran Timberlake. I like some of Gehry's work, like the Loyola Law School. I like modernist work such as that of Eero Saarinen at the Miller House and of many Scandinavian architects who exemplify beauty in simplicity. I am attracted to a lot of European styles--there is something of the clean efficiency and precision of Germany that is embedded in my psyche. I like asymmetry and abstract geometry. I like contrasts, especially contrasts in materials and in the age of materials. I like the detailed work of Scarpa. There is so much to which I have yet to gain exposure; I am still accumulating references.

Suffice it to say, I feel like the whole world is before me, and I'm chomping at the bit to explore it. I know I have a lot of work cut out for me to go there, but I'm looking forward to learning more of who I am as an architect and as an individual in the process.