I am finding that I really enjoy reading architectural theory;

this is a dangerous thing when it comes to writing an analysis of one or

another architect’s work or development of a particular idea. I, at least, cannot assimilate years of

research and philosophizing overnight. I

enjoy getting glimpses of a broad swath of history and the responses of each

architect to the forces at work around them; synthesizing and articulating the

insight I gain from those glimpses is difficult. But I will try to process out loud what I

have gathered in my few readings about Mies van der Rohe and Louis Kahn in

relation to the concept of the open plan.

Mies, it seems, approached architecture in true modernist

spirit, posing a purposeful critique of past and existing modes of building and

design and advancing the development of current architectural thought through

his works. Hartoonian emphasizes the role

that technology played in Mies’s thought and career. Mies saw technology as an important force

throughout architectural history, a key factor in the forms architecture has

taken and continues to take. Inevitably

new technology and materials will give rise to new experiments, new forms. Mies’s works exemplify this process of

experimentation and formulation over the course of his career from more

conservative explorations as in his earlier houses to more extreme examples as in

the Farnsworth House and the Barcelona Pavilion.

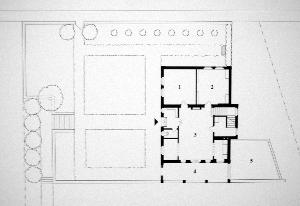

One of Mies’s earlier houses is the neoclassical Riehl House in Berlin, built in 1907. Compared to his later works, it feels basic, almost pedestrian. Its most distinguishing feature is a loggia of sorts integrated with a retaining wall on the side of the house furthest (and not visible) from the street. It seems awkward to me, unexpected and oversized. In plan, rooms are arranged around a central space and the walls are heavy boundaries between them. It is an exploration of the traditional role of walls and columns, clearly load bearing, unambiguous.

One of Mies’s earlier houses is the neoclassical Riehl House in Berlin, built in 1907. Compared to his later works, it feels basic, almost pedestrian. Its most distinguishing feature is a loggia of sorts integrated with a retaining wall on the side of the house furthest (and not visible) from the street. It seems awkward to me, unexpected and oversized. In plan, rooms are arranged around a central space and the walls are heavy boundaries between them. It is an exploration of the traditional role of walls and columns, clearly load bearing, unambiguous.

|

| Plan, Riehl House |

|

| Plans (unbuilt); Concrete Country House, Lessing House, Brick Country House; Mies van der Rohe |

|

| Barcelona Pavilion (1929), Mies van der Rohe |

Taken to its furthest extreme, Mies’s exploration resulted

in the practical elimination of the wall altogether in the Farnsworth House and

his proposed 50x50 House. He questions whether

the wall is necessary at all, whether it can be usurped by the column entirely. Hartoonian talks about how this ardent

exploration led Mies to a conception that left behind culture and the concept

of dwelling. Indeed, this is proved by

the anxiety experienced by Dr. Farnsworth as she attempted to live in the glass

box Mies built for her.

Louis Kahn’s career also plays out a progression of thought

in regard to the open plan, but he starts his work much later, with the work of

Mies and Le Corbusier already well established.

He was born at the time Mies was building his earliest houses and did not

receive an independent commission for a house, the Oser House near

Philadelphia, until 1940. Saito

discusses how at this stage Kahn’s approach to the plan was in typical

modernist vein, subdividing a single volume of space with thin interior walls,

but from the get-go he is conscious of the whole picture, how the individual

room integrates with the other spaces in the house.

It does not take long for Kahn to start moving away from the

single, subdivided volume toward a more room-oriented approach that emphasizes

the individuality of each, though he sticks with familiar definitions of those

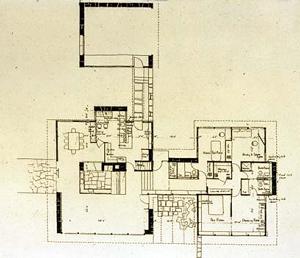

spaces. The plan of the Weiss House (1947-50)

makes this shift clear, separating programmatic zones into distinct volumes

connected via a narrower entryway/passageway.

In a way, this period for Kahn is analogous to Mies’ early period, a

similar exploration of established forms.

|

| Plan, Weiss House (1947-50), Louis Kahn |

Subsequently Kahn began a higher level inquiry, abstracting

the concepts of the room and the house, looking for an order that would allow

the components of the whole to fall into place in a logical fashion. His use of controlling geometries in projects

such as the Trenton Bathhouse (1955) and the Adler House (1954-55; unbuilt) are

the beginning of his critique of the modernist approach to date in the way that

they elevate the room to a defining design element.

|

| Plan, Adler House (1954-55; unbuilt), Louis Kahn |

Goldhagen quotes Kahn from the same time period: “Space made

by a dome then divided by walls is not the same space…. A room should be a

constructed entity or—an ordered segment of a construction system. Rooms divided off from a single larger space

must read as a completed space.” She

goes on to say that to Kahn “the important elements enclosing a space must be immediately

apprehensible, from structure to surface.

For this the open plan was inadequate because partitions, which were

customarily used to mark off spaces, masked a concentrated perception of the

building as a ‘constructed entity’” (Goldhagen 108).

In this Kahn’s development again parallels that of Mies,

though they subsequently went in different directions. Where Mies developed a theory of architecture

around the centrality of construction in terms of technology and its advance

(in constant motion), Kahn developed an architecture around the relationship of

construction to the observer in his place (a static perception). Like other architects of his time, Kahn was

responding to the lack of authenticity he perceived in many aspects of

modernism, which Mies’ work in its ambiguity exemplified.

Kahn’s emphasis on authenticity becomes evident in later

works as he experiments with different types of buildings and the way they relate

to the user. The Salk Institute (1962)

combines the monumental expression of the main structures with his very human

scale moves for the offices that connect to them. At the Kimbell Art Museum (1966-69) Kahn employs

vaulted ceilings resting on load bearing walls, using columns only where the

program needs open space. The open plan

is absent, broken up by the bays of the ceiling—and yet it is kept light and

airy, indeed human, through his innovative toplighting.

|

| Kimbell Art Museum (1966-69), Louis Kahn |

It is interesting to see the progression not only of the

individual architects examined here, but also the progression in modernist

thinking. Kahn is able to pick up the

pieces of Mies’s deconstruction of construction and make something human out of

it. Perhaps Mies saw a shift coming—Hartoonian

notes the presence of “poetics of place” in Mies’ mid-career houses, houses from which

Kahn may well have taken important cues.

References

Colquhoun, A. (2002). Modern architecture: Oxford

University Press.

Goldhagen, S. W. K. L. I. (2001). Louis Kahn's situated

modernism: Yale University Press.

Hartoonian, G. (1989). Mies van der Rohe: the genealogy of

column and wall. Journal Of Architectural Education, 42(2),

43-50.

Saito, Y. (2004). Louis I. Kahn houses (Shohan. ed.).

Tokyo, Japan: TOTO Shuppan.

thank you for this post!

ReplyDelete